What I Learned From Hash Functions

Table of Contents

During 2019-2 semester I had the opportunity to do a research exchange to the US, did some research on Blockchain technologies and took a course on Applied Cryptography.

While I am not going to talk about Blockchain in here, I will talk about Cryptography, hash functions in particular. Before this, I had a very limited idea of a lot of the concepts that are required from hash functions.

Before going there I only had the brief idea that a hash function is a one-way function. Roughfly that you can calculate its output from the input easily, but you cannot get the input from the output.

And with that definition it was enough to know that a lot of security applications rely deeply on them, and a lot of things would not be possible without them, such as Blockchain. But still I had no idea of what they needed to fulfill to be considered a good hash function.

So, without further ado, I’ll dive in.

Hash function #

A hash function is a one-way function \( h \) such that for a given input \( x\in{0, 1}^{n} \), also called as pre-image, gives an output \( y\in{0, 1}^{d} \), also known as image, where \( n \) is of any size and \( d \) is a constant, both are number of bits. $$ y = h(x) $$

Properties #

Now, an ideal hash function has many security properties, but the need for each of them goes mainly on what use it is going to get.

Pre-image resistance (PR) #

Given the output \( y \), it is infeasible to find any input \( x \) such that \( h(x) = y \).

This means that knowing the output \( y \) and the hash function \( h \) it takes a lot of work to find an input that gives us that same output.

The term infeasible in here refers to the fact that you would need a lot of computer power to get the input, and that input may not be equal to the one that actually gave that output in the first place.

Infeasibility #

The size of the output \( d \) should be big enough to make any attacker do at least \( 2^{112} \) attempts of work to break it. This value could change in the future as computer computing capability is increasing.

Furthermore, these properties make the problem even more difficult.

- The output of \( h \) is uniform

The probability of each bit on \( y \) to be either 0 or 1 is 1/2.

$$ \forall i \in {1, \ldots, d} ,; P(y_i = 1) = P(y_i = 0) = \frac{1}{2} $$

Avalanche effect

Given inputs \( x_1, x_2 \) such that \( x_1 \approxeq x_2 \) then \( h(x_1) \neq h(x_2) \) They should differ in at least 50% of the output bits. It should be sufficient to change just one bit.The probability \( P(\text{output} = \text{a specific output}) = \frac{1}{2^d} \)

Collision Resistance (CR) #

It is infeasible to find any \( x, x^{\prime} \) such that \( h(x) = h(x^{\prime}) \)

This means that we only know the function \( h \), an that is it. It should be very hard to find any pair of different inputs such that they are equal.

Weak Collision Resistance (WCR) #

Given an input \( x \), it is infeasible to find \( x^{\prime} \neq x \) such that \( h(x^{\prime}) = h(x) \)

This problem is similar to CR, but it has a key difference: we know one of the inputs, and we are tasked to find another input such that their outputs are equal.

It may seem counter-intuitive, but this problem is harder than CR.

Assuming that the hash function used is well designed to take all of these properties into consideration, a good question to ask would be: what is the minimum size \( d \) from the output to guarantee all of them?

The answer depends on each property, let’s start with PR. Assume that we run \( h \) with \( m \) different inputs. How many pre-images will we find?

Remember, we want an attacker to at least to \( 2^{112} \) attempts.

How many do we need to get at least one pre-image?

$$ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{number of pre-images}] = (\text{number of chances}) \times (\text{probability of a chance}) $$

$$ 1 = m \times \frac{1}{2^{d}} $$

$$ m = 2^{d} $$

[\( m \) should be at least \( 2^{112} \)]

$$ 2^{112} = 2^{d} $$

$$ d \ge 112 $$

Similarly, to get the value for CR, lets do this:

Pick a random \( x_{i} \in {0, 1}^{\ast} \), compute \( y_{i} = h(x_{i}) \), store \( y_{i} \). Does it match any previous \( y_{i} \)? If yes, then halt. Repeat \( m \) times.

$$ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{number of collitions}] = (\text{number of chances}) \times (\text{probability of a chance}) $$

$$ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{number of collitions}] = \binom{m}{2} \times \frac{1}{2^{d}} $$

$$ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{number of collitions}] = \frac{m(m-1)}{2} \times \frac{1}{2^{d}} $$

[We want at least one collision]

$$ 1 = \frac{m(m-1)}{2} \times \frac{1}{2^{d}} $$

[Lets simplify the problem approximating the result]

$$ 1 \approx \frac{m^{2}}{2^{d}} $$

$$ m^{2} = 2^{d} $$

$$ m = 2^{d/2} $$

$$ 2^{112} = 2^{d/2} $$

$$ d \ge 224 $$

Since WCR is a harder problem than CR, then lets set \( d \ge 112 \).

Long story short, we have this constraints for each property:

- No PR, No CR, and No WCR

\( d \ge 1 \) - PR, No CR, and WCR

\( d \ge 112 \) - PR, CR, and WCR

\( d \ge 224 \)

Applications #

There are multiple things that are desirable depending on the application that we need. For this I will briefly describe some scenarios.

1. Server-side authentication #

A common problem addressed with hash functions is the storage of credentials for user authentication, the worst kind of approach that you can do is store the plaintext password in your databases, as this can lead to unintended exposure of passwords from an information leakage, leaving your users insecure, as people usually leave the same passwords in other services and can cause an unintended access to their personal data.

A somewhat better approach to this is to store the hash output from the plaintext password, meaning that you will not know what was the original password used for any user, BUT if you have a data leakage and those hashes get exposed, there is still a way to be vulnerable of knowing the password. Turns out that you can do a dictionary attack, which consists of a table of password-hash pairs with the most common passwords used in web services, that way you can query a password that yields that specific hash, it does not even have to be the same password! as there can be collitions as we already saw previously.

The most common and advised way of dealing with this is to store the hash and a salt value, which is just a random number generated at the creation of the field. $$ \text{hash} = h(\text{password} || \text{salt}) $$

That way a dictionary attack is useless.

2. File integrity #

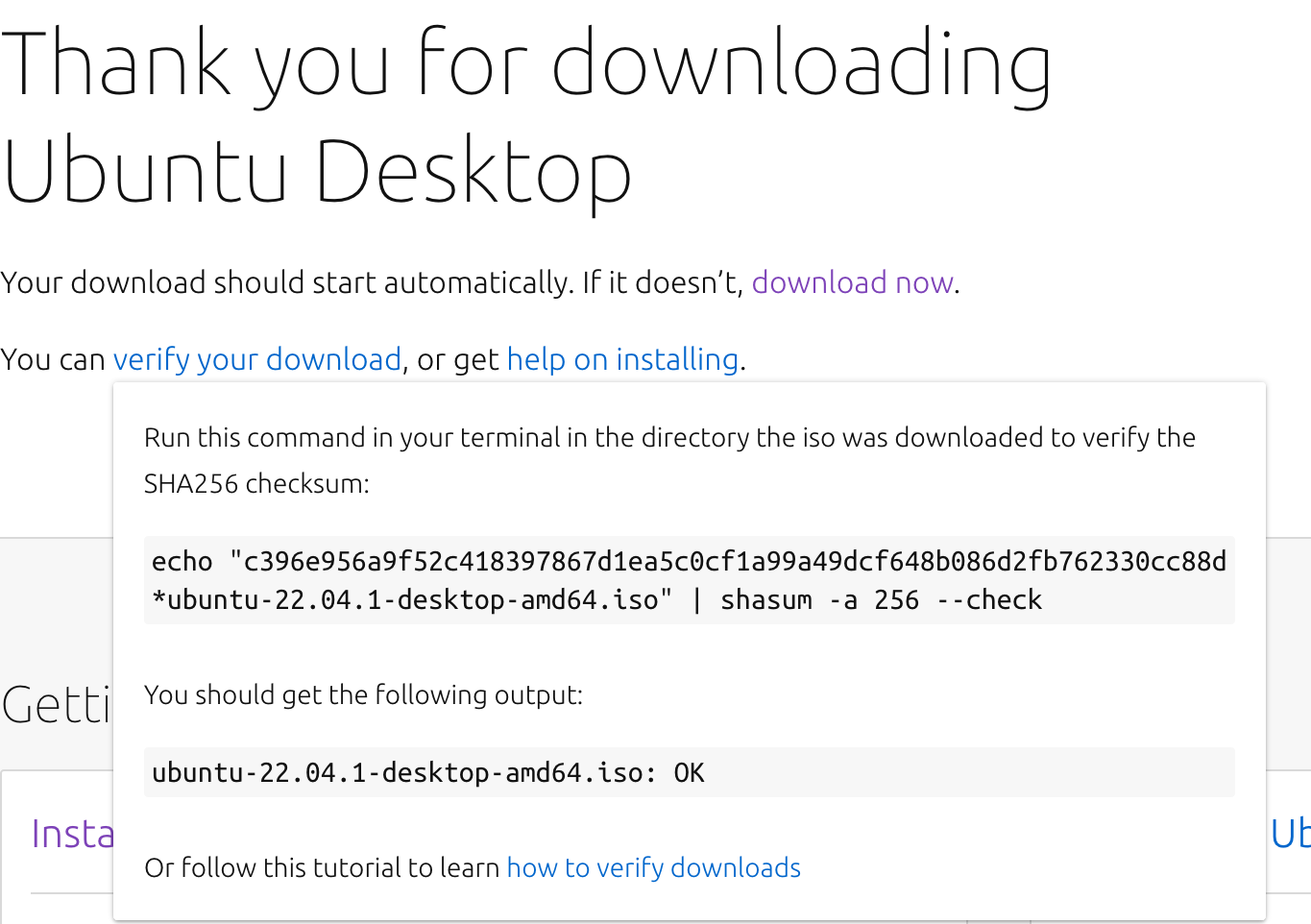

Another common thing to check is the integrity of a file, in this scenario you will have two things: a file and a text file containing the hash value for that file. On common use case for this is when you are downloading a file from the web and for some reason it gets corrupted in transit, therefore there is a lot of places that publish the hash alongside the download button.

Q: What property is desirable for this use case? A: WCR, as we already have the input for the function (the file), it should be infeasible to find another input that yields the same hash output.

Bonus #

There is an additional property not often discussed: Non-malleability.

Given \( y = h(x) \), it should be infeasible to compute: $$ y^{\prime} = h(f(x)) $$ Such that \( y = y^{\prime} \), where \( f \) is a simple function, such as \( h(x+1) ; h(2x) \).

Not every hash function has this property.

Turns out that there is two known types of hash functions with different types of contruction: Merkle-Damgard construction (MD5, SHA-1, SHA2), and Sponge construction (SHA3).

Merkle-Damgard computes the hash iteratably with blocks, processing a chunk of the input information at a time, meaning that an input is \( m = m_{1} || m_{2} || \cdots || m_{l} \), therefore, the hash function iterates through it like this \( y_{i} = h(y_{i-1}, m_{i}) \) and \( h(m) = y_{l} \), each block has a fixed size, if the input size is not a multiple of the block size, there is a padding added at the end that does not alter the output of the entire function (i.e. a bunch of zeros to complete the block).

In particular, Merkle-Damgard construction is susceptible to a Length Extension Attack (LEA), which comes from that padding, in particular if we give the hash function more blocks that are filled with zeroes, it will yield the same result

$$ h(m_{1} || \cdots || m_{l}) = h(m_{1} || \cdots || m_{l} || \text{0000000}) $$

Meaning \( y = y^{\prime} \), violating the property.

Checking this on actual code, if we use a library implementation of these hash functions we can check if this happens. So I set out an example written in Go.

Code

package main

import (

"crypto/md5"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

hash := md5.New()

data := []byte{0x0, 0x1, 0x2, 0x3}

hash.Write(data)

out := hash.Sum(nil)

data = out[:]

fmt.Printf("Before %x\n", data)

moreData := []byte{0x0, 0x0}

data = append(data, moreData...)

hash.Write(data)

out = hash.Sum(nil)

data = out[:]

fmt.Printf("After %x\n", data)

}

Run it with $ go run main.go, assuming that you are in a Unix environment.

Output

Before 37b59afd592725f9305e484a5d7f5168

After 50cca4f19a66632fb7a417364ad05153

Why is this ‘attack’ not working? This kind of scenario was already addressed doing another type of padding, for this Wikipedia already sets a good example of this.

Conclusion #

This was an interesting post to write, not only I wrote about something that I find very interesting, but also something that may be useful/interesting to someone else that may find it, I’m pretty sure I would have loved to find this kind of explanations when I was first dwelving into these subjects.